Guest post by Professor Robin Hambleton.

Mayors and civic leaders from around the world shared their ideas on the future of city leadership at the City Leadership Summit in October. How to lead place-based innovation emerged as a major theme.

Current economic and social trends are creating not only unsustainable cities but also increasingly unequal cities. Globalisation brings many benefits to societies across the world, but city leaders are right to point out that the power of place has, in many countries, been diminishing in recent years.

Place-less leaders, that is, people who are not expected to care about the consequences of their decisions for particular places and communities, have gained extraordinary power and influence. Distant decision makers, because they lack local knowledge, constantly miss fruitful opportunities for investment that can deliver economic, social and environmental benefits for communities.

It follows that an important challenge for modern city leadership is to strengthen place-based power, and to use this power to push forward initiatives that deliver ‘triple bottom line’ results (profit, people and planet). In his presentation to the City Leadership Summit John Elkington explained how forward-looking businesses now assess their performance against 3 criteria:

- economic prosperity

- environmental quality

- social justice

It is no longer just about the traditional financial ‘bottom line’.

In my own presentation, I drew on research carried out for my new book, Leading the inclusive city. Place-based innovation for a bounded planet, to show that, despite global pressures, imaginative civic leadership is alive and well. From Copenhagen to Curitiba, from Malmo to Melbourne, and from Portland to Guangzhou we can find examples of inspirational civic leadership, initiatives that are creating prosperous cities that advance social justice while caring for the environment on which we all depend.

Apart from the importance of strengthening the power of place in modern societies 3 themes should feature boldly in future efforts to improve the quality of city leadership.

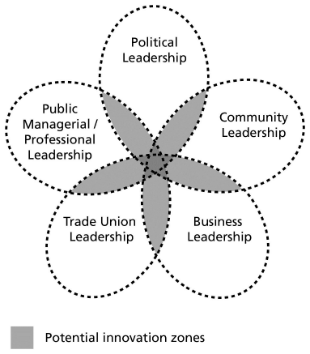

First, it is essential to recognise that effective city leadership involves orchestrating a process of social discovery that brings together actors from the 5 different ‘realms of civic leadership’:

- political leadership

- public managerial and professional leadership

- community leadership

- business leadership

- trade union leadership

It is helpful to view the areas of overlap between these realms as innovation zones - as areas providing many opportunities for inventive behaviour.

Effective city leaders create new possibilities by working across the realms of civic leadership.

Secondly, international lesson drawing now takes on increased importance for city leaders. This is partly because established ways of doing things can be called into question by observing experience elsewhere. City leaders also enjoy the possibility of focussing on actual accomplishments in another setting.

In my book I outline a new way of enhancing the effectiveness of international policy exchange. The approach involves civic leaders in a given city working with scholars and others to co-create an 'innovation story' explaining how radical change was brought about. A useful innovation story is evidence-based, short and draws out clear leadership lessons for others.

For example, in 1978 Melbourne had, according to a local journalist, "an empty, useless city centre". Now The Economist rates the city as the most liveable city in the world. Actors from the various realms of civic leadership shown in the diagram above have played a crucial role in reshaping the public realm.

Thirdly, a key challenge for city leaders is to develop their ability to lead public service innovation. The literature on how to do this is still relatively young. However, a growing number of city leaders are demonstrating new ways of liberating talent within city halls. They set a tone for experimentation and improvisation in public policy making and they value local feelings and identity as they co-create new solutions to pressing public policy challenges.

The creation of the High Line ‘Park in the Sky’ in New York City provides an excellent example of bold public service innovation. The city originally intended to demolish the High Line. However, politicians and public professionals should be praised for learning from local activists about the undetected possibilities for the historic structure. Now the elevated, disused railway has been transformed into a remarkable public park, open to all. In 2014 the park attracted 6 million visitors from all over the world.

Featured image by David Berkowitz on Flickr. Used under Creative Commons.

Sign up for email alerts from this blog, or follow us on Twitter.