Writing some 30 years ago, in her classic study on 'Cities and the wealth of nations', the celebrated North American urbanist Jane Jacobs argued that nations are not the basic economic units, rather cities are. It is in cities that the bulk of a nation’s economic activities are found, where a high proportion of national wealth is produced, and where the majority of a nation’s labour force work and live. National economies, she claimed, can only be understood in terms of the growth of their constituent cities. The performance of a national economy will therefore largely reflect the performance of its individual cities, and how the economies of those cities develop will largely shape the future growth path of a national economy as a whole.

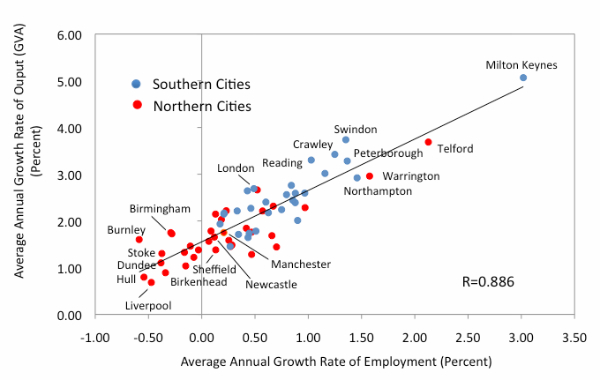

However, our new research on how economic growth has varied across some 63 British cities reveals some worrying trends1. Over the period 1981 to 2011, almost all of the cities in the ‘north’, which includes all of the major conurbations outside London, experienced average annual growth rates of output (gross value added) and employment below the national rate2. Indeed, some of the larger northern cities have grown at less than half the national rate, and some - such as Birmingham, Liverpool and Hull - have actually shrunk in employment terms. Conversely, almost all of the cities in the ‘south’ have grown faster than the nation as a whole (figure 1), and some, most notably Milton Keynes, Peterborough, Swindon, Crawley, Reading and Northampton, managed growth rates 3 times those in cities such as Manchester, Newcastle, Sheffield and Birmingham. And taking the whole period, these smaller, southern cities even outpaced London.

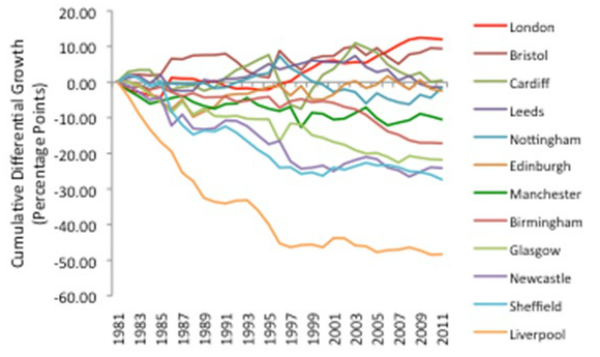

If we consider the major ‘core’ cities together with London and Edinburgh, and examine their cumulative differential performance - the cumulated difference between each city’s annual growth rate and that of the UK as a whole – the scale of the problem becomes only too evident (figure 2). While Cardiff, Leeds and Nottingham have grown at the national rate, Birmingham, Glasgow, Newcastle, Sheffield and Liverpool have all fallen progressively behind, in the case of the first 4 cities by around 25 percentage points, and in the case of Liverpool by almost 50 percentage points. The challenge facing these cities in catching up and closing these growth gaps is considerable. What also emerges is that until the beginning of the 1990s – essentially coming out of the recession of 1990 to 1992 – London’s growth was far from exceptional (figure 2). It has only been since then that London’s growth rate has picked up and has moved ahead of other major cities. This ‘turnaround’ in London’s output growth performance was, of course, propelled largely by financial services, and the banking crisis of 2008 to 2009 has exposed the risk of depending on this sector to fuel future growth: London itself needs to ‘rebalance’ its own economy if it is to maintain a stable and sustainable growth path.

But what of northern cities? Their revival will not be achieved by limiting the growth of London. Economic growth is not some ‘spatial zero-sum game’. There is not some fixed amount of economic growth or activity that has to be distributed across the national space economy. It is not a case of holding back prosperous areas like London and the greater south-east region in order to promote activity in the less prosperous cities and regions of the country. It is, rather, a matter of ensuring that the less prosperous cities and regions are able to realize their full economic potential. To do this they need proper and fair access to the public and private resources necessary to gain ‘second wind’, to use Paul Krugman’s graphic phrase3. And this may well mean that there is a need to examine whether and to what extent economic, financial and political power are too concentrated in London; whether the economic playing field, far from being level, is too tilted in London’s favour.

To this end much greater devolution of economic, financial and political powers to cities and localities is urgently needed. The UK has one of the most centralized public finance systems in the world, and this model is not only unusual but increasingly dysfunctional. Given the imminent devolution of powers to Scotland, a new general mood of more devolution is emerging in our cities4. In his report for the government, Lord Heseltine called for devolving around £50 billion of public expenditures from central government to cities5. Although the government has thus far proved reluctant to relinquish that degree of control, its increasingly recognizing that greater devolution to northern cities is called for.

The Chancellor has announced that he wants to promote what he calls a ‘northern powerhouse’ to rival that of London, via a series of measures, including a possible high speed rail link linking cites on both sides of the Pennines (HS3), devolution of powers to cities to retain local business rates, together with strong ‘metro’ mayors. At the same time, as part of its election manifesto, Labour has promised to devolve £30 billion from central government to local authorities, especially in the north. Unless radical moves in this direction are implemented, it is unlikely that any significant spatial rebalancing of the economy will occur.

The creation of a new ‘spatial literacy’ within government, one that recognizes the enormous potential locked up in cities everywhere across the country, is long overdue. After all, some two thirds of the economy takes place outside London and the south-east. The future performance of the UK economy will depend crucially on explicitly recognizing this contribution and orientating government policy accordingly. Northern cities no less than southern ones are vital to the nation’s wealth.

Let us know your thoughts in the comments below.

Featured image by dan pope on Flickr. Used under Creative Commons.

Sign up for email alerts from this blog, or follow us on Twitter.